Alternative Proteins: The Ultimate Guide

The Fynd

Fresh content for optimists.

Alternative Proteins:

The Ultimate Guide

by Deirdre O.

You can help stop climate change in its tracks in many ways, and choosing alternative proteins over traditional animal proteins is an easy one. Alternative proteins are often better for the planet because their manufacturing produces fewer greenhouse gases while using less land and water than animal proteins. The world of protein is now wonderfully diverse and can definitely send one down a rabbit hole of Google searches for days. To make things a bit more digestible, we’re going to break down how industries categorize proteins by where the protein is coming from—such as plant-based, fungi-based (like our Fy Protein™), algae-based, and even protein grown in labs from animal cells.

In 2020, the alternative protein industry raised $3.1 billion in investment, three times more than in 2019. With the increased funding, comes an increased variety of new and innovative options beyond the currently popular plant-based proteins. Though people tend to use the term “plant-based” to encompass all alternative proteins, that phrase is limiting—as you’ll see, it doesn’t begin to cover the full spectrum of animal-free foods.

The world of alt proteins can be complicated, but once you learn about the types and benefits of these protein alternatives, you’ll be able to confidently choose the right option for you and your family.

Alternative proteins explained

Let’s start with the basics. Alternative protein, also called alt protein, is a general phrase that refers to foods, ingredients, or beverages that have protein derived from non-animal sources. There are six kingdoms of living things—animal, plant, fungi, protists, archaebacteria, and eubacteria. Most alternative proteins fall into the plant, fungi, or protist kingdom. We all need protein to build muscles, repair cells, and provide energy. People choose to eat alt proteins for a variety of reasons, like to help stop climate change, avoid animal cruelty, or eat more consciously.

Plant-based protein

Plant-based proteins are perhaps the most well-known and popular form of modern alt protein and have become very prevalent in the food industry driven by consumers’ demand for an eco-friendly alternative to animal protein. People tend to use the term “plant-based” when referring to any protein alternative in the animal-free space, but the phrase is not all-encompassing. Let’s dive into what exactly plant-based alternatives actually are.

Often replacing traditional proteins in foods like burgers and chicken nuggets, plant-based proteins are made from…you guessed it, plants. The promise of plant-based proteins is similar to fungi-based —they can offer some health benefits and are easier on the planet. With plant-based proteins, you’re concentrating the protein from a plant, meaning that the protein is isolated from a plant (like a pea) leaving everything else behind.

Of course, people can simply eat raw plants, but many of us still crave the taste and texture of traditional meat and dairy foods. Some common plant-based protein alternatives that have been eaten for centuries include seitan, tempeh, tofu, and jackfruit. Plant protein can be made in many different ways. For example, to make a plant-based burger one can grow peas, extract the protein fraction from the pea, and then mix it with other ingredients to create a burger that doesn’t require an animal as the middleman.

Aside from plant-based meat, plant-based beverages like ‘milks’ are beginning to take up a larger number of refrigerator shelves across the globe, with sales increasing 20% in 2020. Many people now consume almond milk, oat milk, and soy milk in addition to or sometimes instead of cow’s milk. So now, if you can think of a food or drink, there’s probably a plant-based version of it.

Fungi-based protein

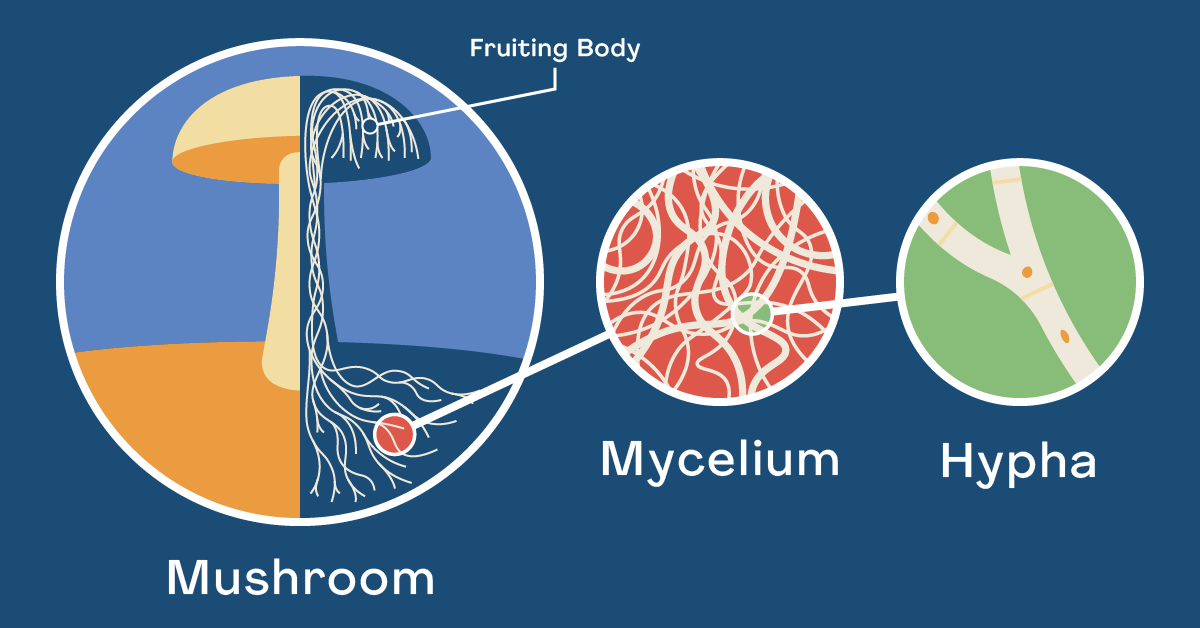

Scientists used to think that fungi were a type of plant, but we now know that fungi fall into their own scientific kingdom and are actually more closely related to animals than they are to plants, even though they’re still stocked in the produce section of your grocery store. Mind-blown yet? In order to fully understand the world of fungi, you’ll have to learn about mycelium.

Most people imagine mushroom caps when they think of fungi, however, that’s just one part of fungi called the fruiting body. Mycelium is a fibrous structure of a fungus that’s mostly hidden from us, spanning thousands of miles underground. Mycelium is made up of hyphae which are thread-like strands that grow into a dense, fibrous structure.

Here at Nature’s Fynd, we make a nutritional fungi protein named Fy™ by fermenting a microbe (more specifically, filamentous fungi) that has origins in a volcanic hot spring in Yellowstone National Park. Because of mycelium’s naturally fibrous structure, Fy mimics the texture of meat, but Fy can also be made into creamy liquids when blended with water and dried into powders, like flour. This versatility allows Fy to be turned into a wide variety of foods like our meatless and dairy-free foods.

And there are several types of fermentation methods—submerged, solid-state fermentation, and liquid-air interface fermentation (our proprietary method). Fermentation uses a fraction of the resources needed to produce plant and animal proteins, though the levels vary based on the type of fermentation. In liquid-air interface fermentation, what’s really unique is that the fungi grow in vertical racks of trays indoors (versus the large tanks needed for submerged fermentation) making it a simpler, more scalable method.

Many fungi-based proteins are inherently nutrient-dense. They’re high in protein and fiber, plus they’re low in saturated fat. As we said before, plant-based protein alternatives just convert an existing protein from one form into another, like from a pea into pea protein into a veggie burger, but fungi-based proteins are truly a source of net-new protein. For example, at Nature’s Fynd the fungi we use actually takes in carbohydrates and turns it into our high-quality protein, Fy, which contains all 20 amino acids, including the nine essential ones. Fy is also non-GMO. Most kinds of animal proteins contain the right combination of amino acids so that people can get all nine they need. But vegetarians and vegans need a varied source of plant proteins—they often have to mix and match non-animal sources to get enough of the right amino acids. A common example of this is the classic combination of rice and beans, each with a set of incomplete amino acid profiles, but together they create a meal with all 9 essential amino acids. More and more companies are entering the fungi-based protein market with a shared goal to provide sustainable foods to a world facing population growth and a climate crisis.

Lab-grown meat

There’s a lot of debate about what to call this next protein alternative. So if you’re new to this space, people also refer to lab-grown meat as clean meat, cell-based meat, and cultivated meat. No matter what you call it, this alt protein is created by growing a few animal cells into fully edible meat alternatives. Companies producing these foods are growing meat from mammals, fish, and even specific animal organs. Plus, lab-grown meat does not require plants for production either.

The growth process typically begins with a couple of animal cells, like stem cells or muscle cells, that are then placed in a growth mixture where they grow on structures called scaffolding. The benefit is that the resulting product tastes like animal meat because it’s grown directly from animal cells. Lab-grown meat removes animals from the equation to avoid abuse and diseases in slaughterhouses while also delivering on the benefit of decreasing the number of greenhouse gases emitted.

Currently, most lab-grown meat companies are in the testing phases, with very few yet in the market. Also, costs for lab-grown meats are still extremely high when compared to their traditional meat counterparts. Until there are more regulatory approvals to scale up and mass-produce lab-grown meats, these costs will likely remain a barrier to mass adoption.

Algae-based protein

Although algae have been consumed and researched for several years, algae-based protein is now becoming increasingly popular in the alt protein space. To make algae-based meats, companies extract a microalga (single-celled organism) and then ferment it to grow an ingredient that’s combined with flavorings to become the final food product. Further, there are different kinds of algae that are used for different applications.

Algae are rich in omega‑3 fatty acids and vitamins. Since these microalgae-based foods are still in the infancy stage of research and only being produced at a small scale, there are many unknowns with isolating and scaling algae-based protein. One challenge this alternative protein faces is that algae lack a neutral smell, color, and taste. Without that, it will likely be difficult to make it a widely acceptable alternative. As research and investment in this field grow, the advantages and disadvantages of creating algae-based protein at scale will become clearer.

Future of food

The future of our planet depends on the future of our food system. It’s exciting that new alternative sources of protein are emerging as they are crucial to nourishing our growing population while mitigating the effects of the climate crisis. Whether your preference is fungi-based, plant-based, lab-grown, or algae-based, when you choose alternative proteins you’re choosing a sustainable option that’s often better for you and better for the planet.

Learn more about fungi-based protein, like Fy, by discovering details about our Meatless Breakfast Patties and Dairy-Free Cream Cheese.

–

1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/p…